The Origins: Why Basel Was Needed

In the early 1980s, banks across jurisdictions operated under widely inconsistent regulatory standards. The 1982 Latin American debt crisis, precipitated by Mexico and several other countries defaulting on sovereign debt, exposed the vulnerabilities of the global banking system. Unexpected losses eroded confidence in cross-border finance and underscored the systemic risks inherent in international banking.

In response, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) introduced Basel I, the first global framework for bank capital. Its goal was clear yet transformative: to ensure that banks held sufficient capital to absorb losses and safeguard financial stability. Beyond technical requirements, Basel I established a baseline for risk management and marked the first effort to harmonize banking standards internationally, laying the foundation for a more resilient global financial system.

Basel I (1988): The Birth of Global Banking Standards

During the 1980s, banks across countries operated under inconsistent rules, often overextending credit with minimal capital buffers. The 1982 Latin American debt crisis (especially Mexico’s default) exposed the fragility of this system. In response, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) introduced Basel I in 1988, establishing the world’s first global standard for minimum capital requirements. Basel I introduced a groundbreaking approach to banking regulation by linking regulatory capital to the level of risk in a bank’s assets. For the first time, banks were required to maintain adequate capital relative to their exposures, setting a global benchmark for prudential oversight.

What Basel I Introduced?

-

Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR): Banks were mandated to hold capital equivalent to at least 8% of their risk-weighted assets (RWA), ensuring they could absorb potential losses.

-

Tier 1and Tier 2 Capital: The framework distinguished between core equity (Tier One) and supplementary capital (Tier Two), enhancing the loss-absorbing capacity of banks.

-

Risk Weighted Assets: Assets were classified by risk categories, incentivizing banks to manage credit exposures more prudently.

| Asset Type | Risk Weight | Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA) Example |

|---|---|---|

| Government Bond | 0% Risk | ₹100 → ₹0 RWA |

| Home Loan | 50% Risk | ₹100 → ₹50 RWA |

| Corporate Loan | 100% Risk | ₹100 → ₹100 RWA |

For instance,

Bank lends ₹1,000 in business loans (100% risk). RWA = ₹1,000 → It must hold ₹80 as capital (8%), split between Tier 1 and Tier 2.

Key Shortcomings of Basel I

Basel I, though revolutionary, had notable limitations. It treated all corporate borrowers equally without distinguishing their credit quality, overlooked operational and market risks, and unintentionally encouraged banks to shift exposures off their balance sheets to minimize capital requirements.

Basel II (2004): Advancing Risk-Sensitive Regulation

By the early 2000s, the global banking landscape had grown increasingly complex. Derivatives, structured financial products, and sophisticated internal risk models became integral to banking operations. Basel I’s standardized approach was no longer sufficient to address these evolving risks.

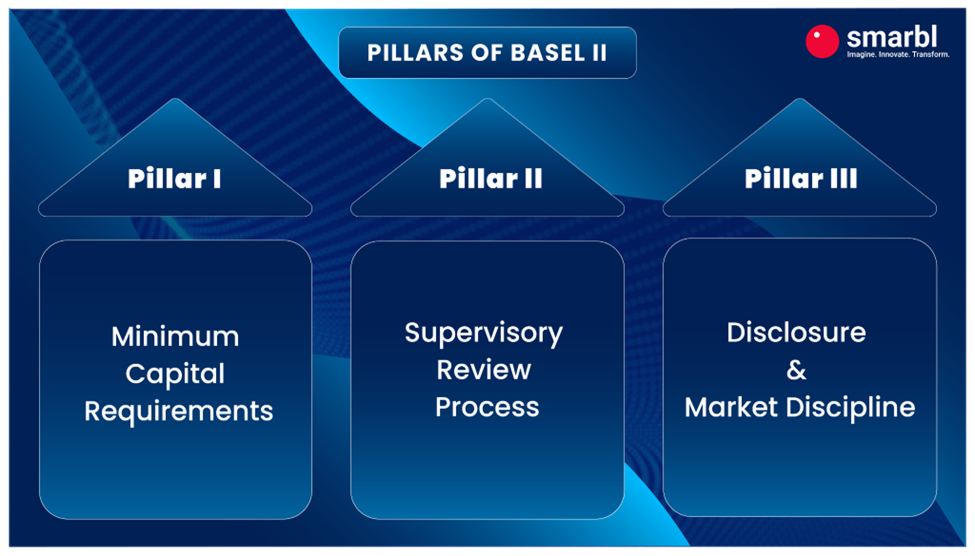

Basel II (2004) aimed for a risk-sensitive, flexible, and transparent approach. It introduced a more risk-sensitive framework structured around three pillars:

Minimum Capital Requirements: Banks are required to hold capital to cover:

- Credit Risk: The risk of borrowers defaulting

- Market Risk: Potential losses from changes in asset values

- Operational Risk: Losses from fraud, system failures, or other operational issues

Basel II also introduced the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach, allowing banks to use their own models to calculate credit risk based on historical defaults, loan exposures, and borrower risk ratings.

Supervisory Review: Regulators assess whether banks are effectively managing their risks. If shortcomings are found, they can require banks to hold additional capital or improve their risk management processes.

Market Discipline: Banks had to disclose key risk exposures and capital information publicly, enhancing transparency and accountability to investors, counterparties, and regulators.

Impact of Basel II

Basel II helped banks strengthen internal risk management, introduced greater transparency and flexibility, and laid the foundation for data-driven regulatory practices.

Key Shortcomings of Basel II

While Basel II represented a significant step forward, its limitations became evident during the 2008 global financial crisis. Heavy reliance on internal risk models and credit ratings underestimated actual risks. In addition, liquidity risk and the interconnectedness of global banks were insufficiently addressed, demonstrating the need for stronger, more comprehensive regulatory standards, setting the stage for Basel III.

Basel III (2010): Strengthening the Core of Banking

The 2008 global financial crisis exposed critical weaknesses in capital quality, leverage controls, and liquidity management. Basel III was introduced to address these gaps and ensure that banks could withstand future shocks while maintaining financial stability.

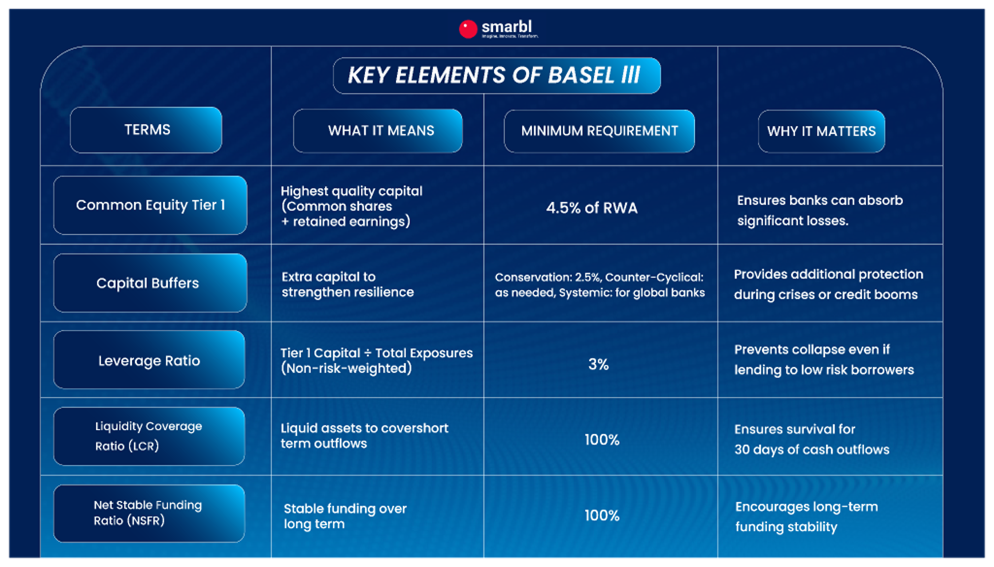

Key Elements of Basel III

Accounting and Data Transformation under Basel III

Basel III aligned risk data with accounting standards such as IFRS and GAAP, driving banks to standardize data definitions (e.g., what counts as exposure), strengthen data governance, and adopt digital reporting formats like XBRL. These measures laid the groundwork for global RegTech solutions and the BCBS 239 data principles.

Basel IV (Basel 3.1): The Road Ahead

Although Basel III strengthened capital, liquidity, and risk management standards, certain gaps persisted. Some banks were able to leverage internal models to lower their capital requirements, creating inconsistencies across institutions. Basel IV, also referred to as Basel 3.1, was introduced to address these shortcomings and enhance the robustness of global banking regulation.

What’s New in Basel IV?

- Revised Credit Risk Approach: Introduces detailed rules for mortgages, retail loans, and commercial lending, factoring in loan-to-value ratios, income, and borrower type

- Output Floor: Banks using internal models must maintain capital at least 72.5% of the amount required by the standard model.

- Standardized Measurement Approach (SMA) for Operational Risk: A single formula for all banks, based on income and historical losses.

- Enhanced Disclosures: Banks are required to clearly explain how capital is calculated and the assumptions behind it.

Rise of RegTech under Basel IV

Basel IV mandates machine-readable reports (XBRL, DPM), traceable risk data, and near real-time dashboards. RegTech solutions help banks meet these requirements by automating reporting, data validation, and governance.

Basel Norms and the Future of Banking

Over 40 years, the Basel framework has fundamentally reshaped global banking. From Basel I’s introduction of minimum capital requirements to Basel IV’s focus on standardization, operational risk, and digital reporting, each iteration has strengthened the resilience of financial institutions and the broader system.

As the financial landscape continues to evolve, Basel norms will remain a cornerstone of prudent banking, guiding institutions in building resilience, protecting stakeholders, and sustaining confidence in the global financial system. From simple rules to sophisticated frameworks, Basel has transformed the DNA of financial regulation.